The writer Pearl Binder once remarked, ‘I always travel slowly and obscurely, on cargo ships and slow trains. I travel for the sake of what I see on the way.’ Today, however, we seem more concerned with getting as quickly as possible from A to Z. How rarely on a train journey do we put down our mobile phones and look out of the window at the passing scenery?

Snakes and ladders

We should not be distressed by lapses from grace. They may well be necessary. We may have been trying too hard, or have become inflated by what we imagine as our progress in the practice of meditation, so that a sudden fall jerks us back to earth. It is like the game of Snakes and Ladders. In our practice we shall, time and again, slide to the bottom of the snake. As Jesus said, ‘No one, having put their hand to the plough and looking back, is fit for the kingdom of Heaven.’ We plod on!

In a dark place

Even in the closest relationships misunderstandings can spring up like weeds, and violence can erupt, with accusations flying back and forth. It is here that the practice of meditation can enable us to look into the eye of the storm and wait for it to pass. As we find in the book of Ecclesiastes, ‘There is a time for words and a time for silence.’ Above all, we should never be afraid to apologise. As the famous Shaker hymn, Simple Gifts, expresses it: ‘To bow and to bend we shan’t be ashamed, till by turning, turning, we come round right.’

The open-eyed meditation

In Rebel Without A Cause, James Dean cries out, ‘But Mom, we are all involved!’ It is no good shutting our eyes twice a day to meditate if we regard it as a retreat from reality. And so, with open eyes, perhaps using as a mantra the words ‘Thou, O Lord, art in the midst of us’, our practice should permeate every aspect of our daily life, whether it is washing dishes, making love, preparing a meal, or taking a child to school. God is in the midst of us.

Healing

Jesus was a man of deep compassion. He was also a healer. Interestingly, whenever someone sought him out to be cured of an ailment, his first question always was, ‘Do you really want to be healed?’ He knew that healing is more than just curing the physical symptoms. The word ‘heal’ is rooted in an older word ‘hale’. To be healed means being made whole, not only a physical level, but mentally, emotionally and spiritually. Deep down the cause of sickness often lies within. Many illnesses are caused by stress, and when we fall ill our body is signalling that something may be wrong with our lifestyle. Only if we remove that cause will we be truly healed.

New year resolution

There is just one resolution above all that we need to make if we practise meditation, and that is to persevere. In season and out. Even when distractions surround us like a swarm of gnats! Our life may seem barren; yet always, deep down, are untapped resources. We have only to reach down into our inner depths and wait for the new life to bubble up.

Lighten our darkness

With the birth of Christianity, the Church not knowing the exact date of birth of its founder, skilfully placed Christmas Day, which heralds the birth of one who would be known as the Light of the World, three days after the Winter Solstice.

The weeks before Christmas are called Advent, from the Latin word advenire, which means to look forward to. What many Christians forget however is the nine month journey of that child in his mother’s womb, a journey that each one of us has made. And with our birth each of us is responsible for carrying a single light for humanity. Lighting a candle at any time is a reminder of the flame within each one of us that we need continually to guard.

A slice of bread and butter

I came across a Jewish story the other day. A man was down on his luck, everything had gone wrong for him, and he was now down to his last ounce of tea, his last slice of bread and a pat of butter. So he thought, ‘I might as well make myself a last cup of tea and have a slice of toast.’ As he buttered the toast it fell onto the floor. But it fell with the buttered side up. ‘That must be an omen!’ he cried. ‘It must mean things are going to change for the better!’

He raced through the village and knocked on the door of the Rabbi’s house and told him the story. ‘It’s a sign, don’t you agree?’ he exclaimed. The Rabbi told him he must deliberate on the matter and that in the meantime the man should go home and come back the next morning.

Very early the next day the man was back. ‘I have deliberated all night with the other Rabbis,’ said the Rabbi, ‘and we have come to the conclusion that you buttered the toast on the wrong side.’

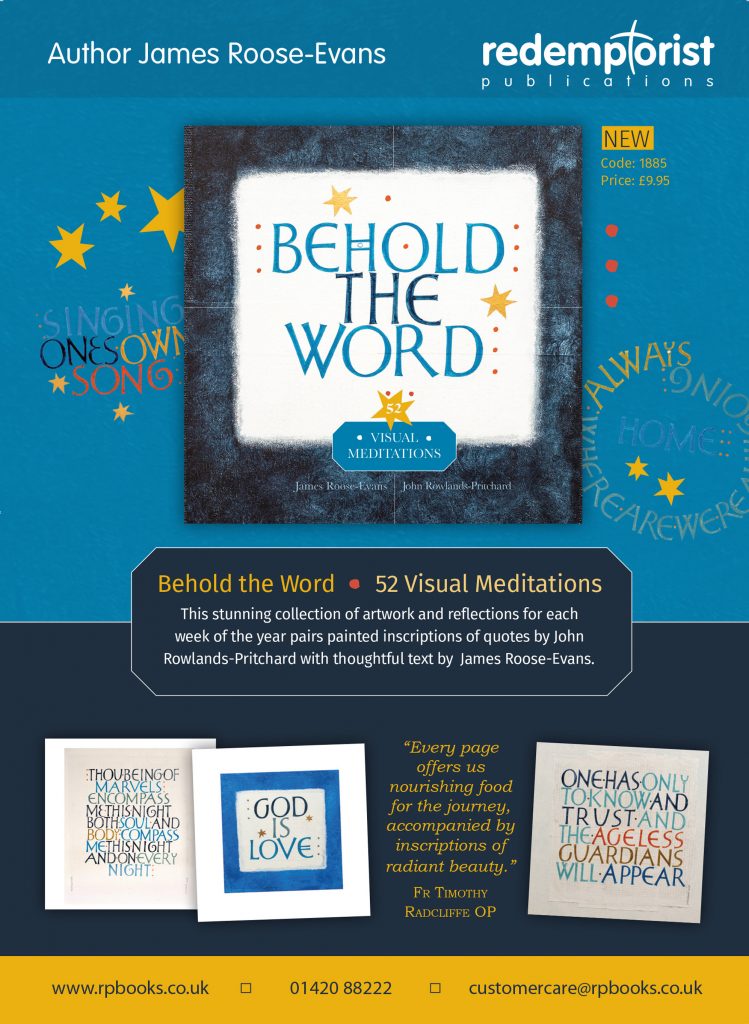

New book by James – Behold the Word

Behold the Word

A collection of artwork and reflections for each week of the year pairs beautifully painted quotes.

Available online: https://www.rpbooks.co.uk/behold-the-word-52-visual-meditations

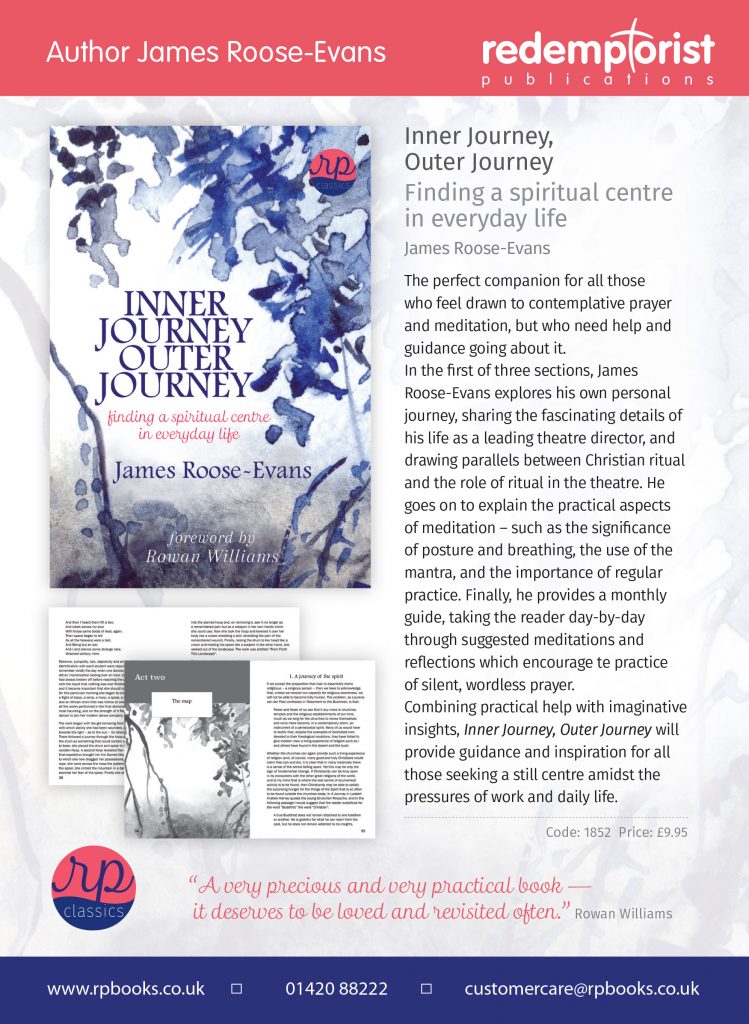

Also from James…

Inner Journey, Outer Journey

Available online: https://www.rpbooks.co.uk/inner-journey-outer-journey

At the frontier

In his journal, Markings, Dag Hammarskjöld, former Secretary-General of the United Nations wrote, ‘Now. When I have overcome my fears –of others, of myself, of the underlying darkness at the frontier of the unheard-of. Here ends the known. But from a source beyond it, something fills my being with its possibilities – at the frontier.’